What celebration can beat the

exuberance and excitement of a wedding festivity? Well, I was soon to find out.

During my engagement to my Teimani (Yemenite) chatan, Eliyahu, it was proposed

to throw the traditional Yemenite, women-only, pre-wedding ceremonial party,

called the Henna. I was warned that it might be more enjoyable than the actual

wedding, and in hindsight, I must agree that it was. I really did not know what

to expect as I was too busy with wedding preparations to check into what

happens at a Henna. I did know what my sister-in-law-to-be told me, which is

that the letters of henna, in Hebrew, stand for the three special mitzvot of a

woman: challa, niddah, and hadlakat neirot.

My

husband’s family explained that, back in Teiman, girls as young as 10 and 12

years of age were married off. This was done for many reasons, including

economic ones. Either way, the young girl was preparing to leave the comfort of

her mother’s home to go live with a man and to be under the influence of her

mother-in-law. During part of the Henna ceremony, the women sang solemn songs

to the girl to express the inner pain of separation and transition that she was

going through.

I

arranged my own Henna to take place a few nights before my wedding in the home

of an adopted Bubby of mine in the Old City of Yerushalayim. I thought of some

creative ideas of how to run the program, until my mother-in-law told me in no

uncertain terms that a Henna is a carefully designed event that is led by

professional women, whom you hire to come and run the show. I was definitely in

for a number of surprises on the night of my Henna.

Amongst

some Teimanim nowadays, a Henna is a mixed-gender party with lots of music,

dancing, and food. I wanted to keep mine a traditional only-women-allowed

event, so the only male invited was my chatan Eliyahu, for the purpose

of taking pictures together. I also preferred a more modest, intimate event

with a small number of family and close friends, doing without a professional

photographer, band, and catered food.

When I

entered my Bubby’s house in the

The

three sisters who were hired to organize the Henna asked me to sit down and

began dressing me slowly and carefully. The custom in Teiman during the Henna

was for the young kallah to be passive and allow herself to be taken

care of by the older women. True to the custom, the women at my Henna outfitted

me in gorgeous, authentic, traditional garb – a special gold dress, matching

gold slip-on shoes, a tall gold-and-white headpiece with huge red and white

flowers surrounding it, dangling beads on each side, and oh-so-much jewelry. I

gingerly allowed them to place several rings on each finger, bracelets to cover

both my arms, and then came the part that I was warned beforehand would test my

strength: the huge heavy metal necklace that, to me, resembled a shield of

armor. The meaning behind the weight of the heavy metal jewelry was to

symbolize the new yoke of marriage. Contrary to what I had imagined, I was

proud to be able to endure the heavy necklace placed on my neck. Lastly, a

bunch of rue branches were placed on the headpiece to protect against the ayin

hara. Rising from my chair, I was transformed into a city-style Teimani kallah.

Later, I would change again into country-style garments and jewelry, for the

styles varied in the different areas in Teiman.

The

ceremonial entrance, known as the zaffeh, which the kallah makes

into the room where her family and friends are gathered to escort her to her

seat, is full of music and ululations. Escorted by my mother and mother-in-law

on either side, I began my slow walk out of the room. The Teimani organizers

stood a few steps ahead of me and beat on drums and large gold plates to the

rhythm of the music. All those gathered around were dressed up too – in black

robes with gold-and-red decorations at the top, covering their heads. Some were

holding large decorated plates with flowers along their rims and colored

candles inside, while others held tall vessels filled with flowers on their

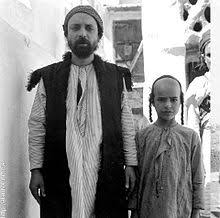

heads. After my slow walk to my beautifully-decorated chair, my chatan

Eliyahu made his appearance, dressed in a matching golden robe, a colorful

scarf draped over his shoulders, and a Teimani-style turban on his head, which

is what the Jews wore in Teiman. Artificial peyot, known as “simanim”

were placed under his turban, and presto, we got a replica of a Teimani chatan.

Aside

from the dancing, singing, and merriment that filled the night, the traditional

Henna could not be replete without putting the henna plant on my hand and on

the hands of anyone else that wanted a bit of the pigment. My mother and

mother-in-law were invited to knead the henna paste. After placing some paste

into my hand, I squeezed it shut for several minutes to allow my skin to absorb

the red color. It was explained that the henna is another protection against

the ayin hara.

It was

some night, an occasion to be remembered and treasured. I enjoyed this Teimani

celebration even more than our wedding, which was a more typical Israeli-style

event. At our wedding, the band played Teimani music for several minutes, and

my husband’s family enjoyed Teimani dancing, called tzad Teimani. Over

the next few months, while staying indoors during

Although

Eliyahu follows halacha according to the Shulchan Aruch, as the Sefardim do,

and is not all that interested in Teimani culture, I was surprised when he

decided to buy parchments with minhag Teiman for the mezuzot on

the doors of our newly rented apartment. have small differences on how the

letters are written. So, we went to Bnei Brak, to a store that sells parchments

and all kinds of Teimani Judaica, jewelry, and music. I chose some disks of a

popular Teimani singer, Chaim Yisroel, that I enjoy listening to. Since it was

before Purim, I asked the storekeeper if he had Teimani garb for me to wear as

a Purim costume; unfortunately, he didn’t. Instead, I chose a pair of

Teimani-style earrings. Eliyahu was more fortunate and walked out of the store

with a Teimani-style robe and turban to wear on Purim.

After

Purim, the next time that I was reminded that I had married a Teimani man, was

when Eliyahu expressed a desire to have a Teimani Pesach Seder since we had to

stay by ourselves for the chag because of

My

mother-in-law kindly wrote down exact instructions and messaged them to me. The

maror consists of washed lettuce leaves, which are placed around the

edges of the table as a border. Teimanim don’t prepare horseradish. Onions and

parsley leaves are interspersed amongst the lettuce to be used as karpas,

instead of the traditional potato and celery that I was used to. Then, inside

the lettuce-leaf frame go the rest of the foods: the roasted bone, egg, and charoset

made from wine, dates, nuts, and black pepper! I lacked the other ingredients,

raisins and hawaij, a popular Teimani

spice, but it turned out that it was the first time that I enjoyed the taste of

charoset! I also set up the wine – yes, the Teimanim also drink four

cups – and the matzah. I was disappointed that this year I would not be able to

taste Teimani matzot because we were trying to stay in the house as much as

possible. In past years, Eliyahu’s brother would make these matzot by hand, and

they are more like lafa-style pitas than the cracker-type matzahs Ashkenazim

eat.

After

setting up the Seder table, I was fairly proud of the way it looked, but then I

was told that I should put a tablecloth over the table to cover all of my hard

work. Well, that’s what the Teimanim do! They cover the table until it is time

to eat the matzah and maror and then uncover it. I put up a bit of a

fuss but acquiesced, wanting to do things the right way according to my

husband’s traditions. The only other Teimani food I prepared for the Seder was

my mother–in-law’s chicken soup recipe, called fetoot. This entailed

soaking the chicken in boiling water before cooking it, and step–by-step

instructions of the order of putting in ingredients, such as onions and

vegetables. After the soup is all cooked, some broth is removed and carefully

mixed with a bit of flour it to thicken it. Lastly, pieces of broken matzah are thrown in that I

imagined would be soggy and unworthy of eating, but Eliyahu was really excited.

I gave the soup a chance, and was surprised at how delicious it was!

All in

all, I don’t have to adapt to too many other changes now that I have entered a

Teimani family. Even before meeting Eliyahu, I had started preparing a dip for

Shabbat called chilbah, which is fenugreek seed mixed with greens and

spices. I recently started using the Teimani spice hawaij to season soups, fish, and chicken. When we go to Eliyahu’s

parents for Shabbat, there are a few other differences that Eliyahu doesn’t

practice. For instance, one man says the birkat hamazon at the end of

the seuda, and everyone else listens and answers amen to be yotzei.

Another Teimani custom is to serve ja’ale, tasty nuts and seeds that are

served before beginning a celebratory meal.

It is

when I am in Eliyahu’s childhood house with his parents that I am led to

reflect on the Teimani man I married. Stepping out of one’s culture to enter a

new one can be seen as exciting or uncomfortable. I am grateful that my in-laws

are accepting and wanted me as part of their family ever since we met.

The

challenges that I encounter at times are inevitable. Although I am learning

Hebrew even more fluently now that I am speaking it at home, there are moments

that we don’t understand each other smoothly because of language differences. I

think that marriage is always a bit of an unknown journey, and I continue to

believe that what supersedes all is the ability to appreciate one another’s

personality and character.

I

truly hope that every heart in Am Yisrael will open to see the beauty in

each other, no matter which continent one is from or what culture and customs

one keeps, or what language one speaks. I believe that with my return to Eretz

Yisrael and that of Eliyahu’s parents we merited to join together to fulfill

what was written by the students of Harav Avraham Yitzchok HaKohen Kook: “Our

true life is as a klal, and not as a collection of individual Jews.” (Lights on Orot, pg. 16)

Baruch Hashem, after over 2,000 years of galut, Yemen

has finally met Balt