If you would have heard me say, about a year ago, “Until 120,” you might not have known that it referred to something other than a wish for long life. That is because I was searching for my soul mate and getting rather weary. Most of my dates were coming from the two Israeli dating sites I had joined. Many evenings I would closet myself by the computer and tell my friends I was going “shopping,” that is, navigating the dating sites to see whom I could get a date with. The sites have more than 40,000 members, so choices were plentiful. The problem was that, although many guys I met really were suitable, I had also encountered a fair number of disappointing dates.

Choosing to use my wits as I was approaching my meeting with Mr. 115, I decided that setting a deadline might be a good solution to the seemingly endless maze I was in. Hence, I made a plea to Hashem – and told my close friends – that I would put in effort until Mr. 120. If after meeting him, it was still not right, I would retire to backstage and focus more on other matters in my life.

Well, getting to Mr. 120 was definitely not an easy ride. I counted numbers 117, 118, 119…and then I paused. Who would be Mr. 120? I felt anxious and curious, hopeful and excited. It seemed as though, lately, every time I got close to going out on my next date, the situation would turn around at the last minute, and either the guy wouldn’t be interested in meeting or there would be some mistake. Part of me was frustrated that nothing was working out anymore, until I reminded myself that the next guy I dated – I wanted him to be my husband, not just another man to go out on a date with. So, I lifted my chin and back to my dating sites I went.

On Thursday night, I hit gold! I had found an amazing profile of a handsome man, who, although several years older than me, actually looked normal and whose self-description intrigued me to find out more. One thing we had in common was that he was living in Gush Etzion, where I had recently lived. I tried not to get too excited after giving him my telephone number and hearing his affirmation that he would call me the next day in the afternoon. Friday morning I busied myself, but as the hours went by, disappointment started to creep up as I imagined that he was not serious after all and would not contact me as he said he would.

To my utter relief, Mr. 120 did indeed call that Friday afternoon and a date was arranged for Sunday evening. Yes, when I saw my date, Eliyahu Shai, for the first time, waiting outside his car to pick me up, I was impressed. I saw that he was a good guy: He came to pick me up and treated me nicely. I even wondered if he would indeed be my husband – until the moment we were sitting at a restaurant table, and I popped a question that suddenly occurred to me to ask.

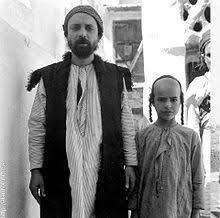

I had happily assumed that Eliyahu was Sefardi because of his Middle Eastern look in his profile pictures. Although I come from an Ashkenazi background, my wish was to marry Sefardi. I love their tefilot, their warmth, their food. But then, as I was looking at this man I was dating face to face, I started to doubt that he was Sefardi; he actually looked very Teimani, Yemenite. Now, I had said on a number of occasions after meeting Teimani guys that, although I respect them for who they are, I did not want to marry Teimani. Their tefilot and pronunciation is very different from that of both the Ashkenazi and Sefardi communities, and I drew a mistaken conclusion that a pattern of what you might call “personality” that I had seen from a few other Teimani dates was not for me. So, that evening when Eliyahu told me that he was 100% Teimani on both sides, I had to restrain myself from making a run for it. I told myself sternly to be fair and give him a chance. As they say, “You never know!”

Well, Hashem has a way of showing Who is in charge. I felt something pulling me to continue dating Eliyahu, and as the months went by, I realized that the thing I hated the most was when he dropped me off at the end of the date and said goodbye. There were many ups and downs in our dating, and each time I felt ready to pull out, Hashem would send someone to give me the exact advice I needed, the exact tip in the book I was reading on dating that I needed to implement, or just the very scenario I needed to push me back into the arena.

Even after I came to a decision that

I wanted Eliyahu to be my husband, it was hard for him, at the age of 40, to

commit. So we kept up our relationship, until one night, he surprised me with a

piece of jewelry and asked me to marry him. Baruch Hashem, we celebrated

our wedding about two-and-a-half months later in a nice hall in the yishuv

Mitzpe Yericho, right before the

* * *

Although Eliyahu and I have a lot in common, like our strong passion for Torah and Eretz Yisrael and our love of hiking and nature, we also have many differences, just like every couple. However, I don’t think that these differences are because he comes from an Israeli Teimani background and I come from an American Ashkenazi family. I believe that, although cultures as well as customs/minhagim vary, it is the individual’s character and personality that are defining.

In fact, as I got to know Eliyahu

and he shared more of his outlooks with me, I learned that I am often more

interested in his family traditions than he is! Both of Eliyahu’s parents

immigrated to

Notwithstanding his Teimani upbringing, Eliyahu was sent to boarding school as a teen and melted into a typical Isaeli framework, leaving most of his own culture and customs behind. Being in an environment unlike his family’s from an early age taught Eliyahu that if he were to maintain the Teimani pronunciation he would sound very different than his peers and they would most probably not even completely understand him. To appreciate this, a little background about Teimani Jewry is needed.

* * *

It is often mistakenly assumed that the Teimanim are just

another sect within Sefardi society, that there are communities from

The Teimanim stand apart from other

Mizrahi (Oriental Jewish) groups, known in general as Sefardim. The name comes

from the Hebrew word for

One is the Baladi group, which means “country” in Arabic (the spoken language in Teiman). They are called Baladi because they stick to their original nusach of tefila and go according to their own ancient traditions as well as the halachic rulings the Rambam laid out in the Mishna Torah. A strong bond of love and trust was developed between the Jews of Teiman and the Rambam during the late 12th century, when Teimani Jewry was undergoing persecution from their Islamic rulers and mass confusion from a strong influence of a false Mashiach. It was then that the Rambam wrote the Igeret Teiman, a letter to encourage Teimani Jews to adhere to their traditions and withstand their hardships. He also praised them for their strict adherence to mitzvot and halacha that they had received from connections that they forged with the Geonim in Bavel. Henceforth, the Jews of Teiman looked upon the Rambam as their spiritual leader.

A few hundred years later, in 1678, the King of Teiman expelled the Jews of the city of Sana’a to the torturous heat in the desert of Mawza, where many Jews died of starvation and disease. Upon their return after about a year of intense suffering in exile, a new development unfolded for Teimani Jewry. A large segment of Jews began to be influenced by the new siddurim with Eidut Hamizrach being sent to them from the Land of Israel and Sefardic countries. They were also influenced by the rulings of the Shulchan Aruch, which had been predominantly accepted by other Mizrahi sects. Wanting to be part of the mainstream, they followed suit. Even so, this group maintains the unique Teimani pronunciation, chant, and minhagim. The latter group became known as Shami, in Arabic “ash Sham,” the North, referring to Greater Syria and the Land of Israel, from where the siddurim were sent.

Both Baladi and Shami Teimanim are known to stand out in their preservation of traditions. Many are of the opinion that Teimani Hebrew is the most ancient and thus the most accurate form of the language. Almost every Hebrew letter has its own sound, such as the gimmel, which is pronounced jimmel. Another thing that stands out in Teimani tradition is that Targum Onkelos, the Aramaic translation of the Torah, is read aloud by a boy during the Shabbat Torah reading in shul.

* * *

So it was not for nothing that Eliyahu decided to blend into mainstream Israeli religious society. As he matured, he took on nusach Sefard as his nusach. He had come to appreciate the significance behind the nusach, which was created by the Arizal, who desired that all of am Yisrael should unite to daven the same nusach. The Arizal therefore took from nusach Ashkenaz and Eidut Hamizrach and merged them into one siddur. Since achdut (unity) is a central value for Eliyahu, he was drawn to take upon himself to daven nusach Sefard.

After our wedding, I immediately began davening from the new siddur I had bought: nusach Sefard. Switching to nusach Sefard was exciting for me as I enjoy the beauty of the added words I was now saying in different sections of my tefilot, and I was forced to read the words much more slowly and carefully until I got used to my new siddur.

In the same vein, when it comes to keeping halacha, Eliyahu goes according to the Shulchan Aruch so that he is more connected to broader Jewish society. Although I conceptually appreciate Eliyahu’s outlooks, I am sometimes left feeling a bit confused since I do not yet know the differences of halacha. But when all is said and done, I am grateful that Hashem has led me on this Teimani path. Bezrat Hashem, in the next article of this series I will share some of the perks in Teimani culture.

Masalama, goodbye for now!

Historical information from Wikipedia.com.