|

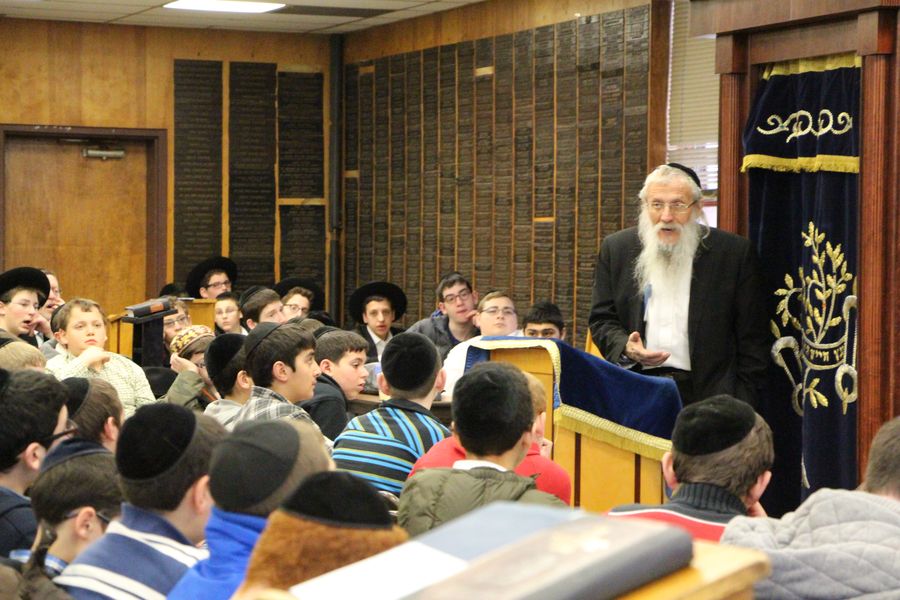

Neither rain, nor snow, nor gloom of night could keep the crowds away from Shomrei Emunah Sunday night. A large, diverse crowd came out to hear famed Russian refusenik R’ Yosef Mendelovich talk about his experiences fighting for Soviet Jews behind the iron curtain as part of his tour which included speeches at Beis Yaakov and Torah Academy as well.

In 1970, R’ Yosef and a small band of his friends decided they were going to escape the Soviet Union. Masquerading as a wedding party, they bought out all the seats on a small plane flying from Leningrad to Priozersk, near the Finnish border. The plan was to tie up the pilots and leave them on the runway after landing in Priozersk. Mark Dymschitz, a former army pilot who had come up with the plan, would then fly the plane to safety in Sweden, keeping low to avoid radar detection during the short flight.

The plan sounds desperate, but it would be difficult to think of a better one. Emigration from the Soviet Union and movement within the country were heavily restricted. People were registered to a particular house in a particular city under the “propiska” system, and had to get official permission to move elsewhere. The entire western border was enclosed with a wall, and patrolled by armed guards. Maps of the country were even deliberately distorted to make it impossible to navigate with them, with rivers in the wrong places and streets missing or mislabeled.

All these measures combined to make emigration effectively impossible, and even travel within the country was extremely difficult. You couldn’t simply walk into a train station and buy a ticket: you would have to explain where you were going and why. Hijacking a short flight near the border was a plan that might have a chance of working.

But the fact was that they had very little chance of success, and they knew it. “As someone who had already served time and not the stupidest person on the planet, I understood, of course, that it was a hopeless matter,” recalls Kuznetsov, in an interview with Yuli Kosharovsky, author of the book We Are Jews Again. “We had sixteen participants. In order to reach this number, it was necessary to speak with hundreds of other people… a leak was inevitable.” They went ahead with the plan anyway, out of desperation and a desire to bring attention to the plight of Soviet Jewry.

On June 15, 1970, the “wedding party” arrived at the airport. They could see the soldiers hiding in the bushes and behind buildings all around them as they approached the plane, but they continued ahead anyway. The KGB’s omnipresent spy network had been tracking them for months, and an entire regiment of border guards had been brought in to arrest them in a grand show of force. The would-be hijackers quickly found themselves awaiting trial in separate cells.

The KGB’s plan was to get them to confess to treason and publicly apologize for their actions, in the hopes of crushing the spirit of other refuseniks around the country, a movement that was beginning to gather steam in the hearts of Russian Jews. Ever since the Six Day War, these Jews who had so long been isolated from their brethren were beginning to take pride in their Jewishness once again. By getting these heroes of the movement to renounce it, the KGB hoped to crush the rebounding Jewish hopes, and force the refuseniks back into passivity.

R’ Yosef’s interrogator wanted to help him out. “You remind me of my brother,” he said. “You’re a good Russian at heart, I can tell. Why would you fight us? Give us some names, confess your treason, and you’ll get a lighter sentence. I don’t want to see you get the death penalty. Do the right thing here.”

R’ Yosef had his own ideas of what the right thing to do was. He’d been becoming more religious in the year leading up to the hijacking, but now, in prison, his religion became a focal point for his struggle. He wanted to show the “good cop” that they weren’t the same, partly to remind himself of the same thing. Taking a handkerchief, he tied the ends together to make it into a yarmulke, and wore it to his next interview. The interrogator wasn’t amused, and R’ Yosef’s point was made. This man was not his friend- they were enemies.

He committed other acts of “civil disobedience” while in prison, such as praying and keeping Shabbos.

When Chanukah arrived the Leningrad hijackers were brought to trial. The idea was to make a show trial, to undermine the movement by having them renounce it, but the plan backfired. One after another, the prisoners accused the government of anti-semitism and tyranny, denouncing the system for its mistreatment of them. The trial was a victory for the refusniks, but the participants were handed very severe prison sentences of up to 15 years. R’ Yosef, as one of the leaders of the plot, got 12 years. Mark Dimschitz, the organizer of the plan, and Eduard Kuznetsov, already convicted of an earlier offense, were sentenced to death.

The death sentences sparked outrage in Jewish communities around the world. The Leningrad trial brought the plight of Soviet Jewry to the attention of the Jewish community at large. Meanwhile in Europe, the conviction of several Basque terrorists to death sparked protests across the continent, and the protesters called for the Soviets to rescind the death sentences of Dimschitz and Kuznetsov as well. All this pressure eventually resulted in the Soviets dropping the death sentences to life in prison. Later, these sentences were reduced even further to 15 years apiece, and both men eventually managed to emigrate to Israel.

As a result of the scandal and public pressure the Soviets began allowing Jews to emigrate. In 1971 over 12,000 Jews were granted permission to emigrate to Israel, after only 999 the year before.

R’ Yosef’s neighbor in prison shouted the news of the reduced sentences to him through the wall. Soon after he was transferred to a work camp where he was to serve out his sentence. Throughout his stay, he kept up his struggle to keep the Torah, fashioning a yarmulka from a pair of pants and arranging kosher food for the Jewish inmates with the help of a Ukranian nationalist cook. Somehow he managed to smuggle in a siddur, which he copied onto small pieces of paper he hid in a matchbox.

Shabbos was especially difficult. R’ Yosef and the other prisoners managed to arrange with a Ukrainian overseer to cover for them for not working on Shabbos, while they would try to keep out of sight of the guards. One Shabbos, R’ Yosef was hiding in the snow when he heard footsteps approaching. Looking behind him, he saw the overseer of the entire camp, Major Federov, coming right towards him.

He was sent to the punishment room, where he stayed for weeks. Every Shabbos, Major Federov would offer to let him out if he would go to work, and every week he said no. Eventually his stubbornness landed him in court again, where he had three years added to his sentence for violating the rules of prison, and was transferred to a criminal prison where everyone was kept in separate cells. Now keeping Shabbos was easy, as he didn’t have to work.

In 1981, after 11 years in prison, R’ Yosef was finally released, and the Russians immediately revoked his citizenship and expelled him from the country. He joined the 300,000 Russian Jews who had preceded him to Israel.

R Yosef Mendelovich is now a rebbi in Yeshivas Mechon Meir in Jerusalem.

Pictures by Shlomo Pollock